Current Nature: Inside A Bird's Winter Survival Kit

This winter, the cold on Nantucket has been particularly intense. In recent years, many of our winters have been relatively mild, with open water lingering well into January and February. This year, the harbor froze so thick that the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter had to carve a path for the ferries. Watching that happen makes you realize just how locked in the island can become. For us, it means ferries that cannot run and plans put on hold. For birds, it means moving, gathering, and adapting to the cold.

Current Nature: Weathering The Storm

These winter storms have pummeled the island, delivering frigid temperatures and a blanket of snow that has since hardened into an icy crust. While many of us have faced the maddening tasks of shovelling out our driveways and defrosting cars, what has nature been up to? How have our flora and fauna fared? Surely this major snowfall has impacted the natural world… or has it?

Water, Water, Everywhere, But…

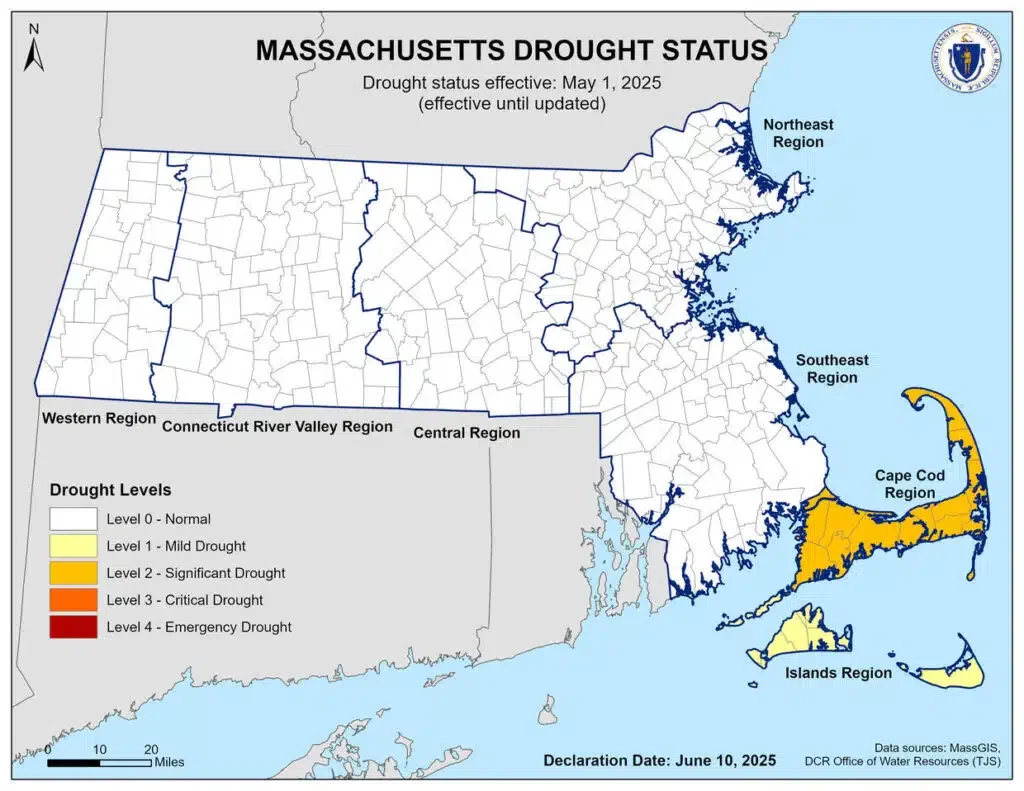

In June 2025, Nantucket was placed under a Level 1 drought by the Massachusetts Drought Management Task Force, prompting mandatory restrictions on outdoor water use. Then, over last weekend, we learned that the town’s primary water pump suffered a mechanical failure, leaving the island’s water storage tank at “critically low” levels. The ensuing water use ban has included all non-essential water use, and applies only to properties connected to the municipal water system.

A Pine Time On Nantucket

My time on Nantucket began late spring in the pitch pine forest at Lost Farm and with the quiet solitude of shorebird monitoring before the busy season. During my free time, I took the chance to explore the different areas and habitats here. On an island that is less than 50 square miles, the diversity of habitat and resilience of plantlife and wildlife is truly amazing.

71st Nantucket Christmas Bird Count: 133 species And 61,455 Individual Birds

Snow, frozen ponds, and bitter cold did not stop Nantucket’s birding community. On December 28th, volunteers bundled up and went into the field for the 71st Nantucket Christmas Bird Count (CBC), as part of the National Audubon’s Society’s longest-running community science program. For the count, the island is divided into eight designated sections and the birders spread out across them, covering coastal habitats, woods, grassland, neighborhoods, and backyard feeders across the island to record all the birds within a 24-hour period.

Current Nature: Rain, Rain, Come To Stay - How We Measure Precipitation On Nantucket

Of all the places I’ve lived, Nantucket is one of the most attuned to daily weather and climatic patterns. It likely has something to do with the maritime past, but, even today the island’s food, mail, and ability to come and go as we please is dictated by weather - it’s full community awareness.

Current Nature: A Soaring First Year For The Nantucket Osprey Watch

As Nantucket’s Ospreys take to the skies and begin their journey south, we pause to reflect on what has been an incredible first season of the Nantucket Osprey Watch.

Current Nature: Black Tupelo Beauty

Attending The Ohio State University, I spent much of my undergraduate experience working in the hardwood forests that dominate the East Coast, walking under towering black cherry trees in a forest that would seem to continue forever. It was a memorable shock when I arrived at Nantucket and those same 60-foot-tall, thickly barked trees were here in a completely new form.